Mar 20, 2019

THE TWO-FOR-ONE TURKEY SPECIAL

The screen door slipping from my hand and slamming the frame causes a cacophony of gobbles up and down the ridge below the cabin. It was purely an accident that I made so much noise. I’m young, but in hunting, you must remain quiet at all times, I know. And I guess you’d count exiting the house and heading into the woods the beginning of the hunt.

My dad stops to listen as the gobbles continue. He turns his head. I think he’s looking at me. I assume he’s grinning. He probably knows I’m about to kill two toms with one shot because my dad knows everything.

Daylight is barely visible in the east, and the woods are just starting to wake up. Sparse calls of cardinals and tree frogs, woodies down by the river. A brace of Canada geese sparks another volley of thundering gobbles. A hen or two interjects.

There used to be a lot of turkeys on our farm in south-central Tennessee just outside of Lynchburg where, on winter days when the wind is blowing steadily out of the north, you can catch whiffs of the sour mash used to make Jack Daniel’s whiskey cooking. Folks said the game wardens began trapping and relocating entire flocks. Then, coyotes got the blame. Then raccoons. Now, it’s the chicken farms where a bacteria that grows in a chicken’s feces is raining hell down on the avian world. Coyotes and raccoons and the others are just speculation until proven otherwise.

Back then the privet down by the spring wasn’t so thick. Nothing much to snag a sleeve, scratch a face or detach the seat from a turkey vest. The spring flowed well too, still does, in fact, and helps mask your boot rolling a rock or breaking a twig, things that happen moving through the lightless woods.

My dad and I ease through the creek bottom and up the other side to a pasture surrounded by woods on three sides. We turn right, continuing downhill, and enter the canopy of trees again. Just inside the treeline, we’re no more than a couple hundred yards at most from the roosting turkeys. They’re quiet. I’m worried they hear us.

“Son, find ya a tree over to the right and I’ll do the same back here.”

“Okay.”

“Be sure it’s wide enough they can’t silhouette you.”

“Okay. Think they hear us? They’ve shut up.”

“Doubt it. Just sit there and be quiet and still and we’ll see what happens.”

Turkey hunting was easy for me as a kid. Not that we were super successful, we weren’t. Between my dad and me, mostly me, we’d always find a way to screw it up. I was fidgety in my younger years and lacked an important quality a hunter needs: patience.

But this morning all I have to do is sit there with my shouldered shotgun resting across my right knee as my dad pulls out his go-to H.S. Strut Push Button Yelper and gives a soft yelp.

Gobbles erupt. I don’t mean four or five within earshot. I’m talking about what sounds like four or five for every tree that runs the duration of the ridge. That’s an exaggeration. But everything in the world is bigger to kids.

It’s still early so we sit and let the woods come around naturally. The darkness plays tricks on my eyes. Did something move? I turn my head to peer out of the corner of my eye as I’ve done on a thousand pre-dawn mornings, not knowing peripheral vision offers better sight at night. It’s simply a natural reaction.

I close my eyes. It’s hard to hold them shut. The anticipation is so high I have to remind myself to breathe. I know something good is going to happen. It’s like setting the hook of a spinnerbait a split second before a largemouth bass strikes. You just know.

The sun creeps steadily toward the horizon. It’s light enough where I can see about 50 yards. Dad calls. A lot of gobblers hammer back. A set of wings flapping. Whether they’re stretching on the limb or flying down isn’t readily apparent. “Breathe,” I tell myself, my throbbing temples and blurring vision are the ultimate reminders that oxygen is required to function.

Then I begin to hear it. Putt-waaahhhhh. Putt-waaahhhhh. Putt-waaahhhh. For some reason, it’s an irregular drumbeat. One gobbler’s approach typically yields a pretty even tempo. But when six are coming to the call at the same time…

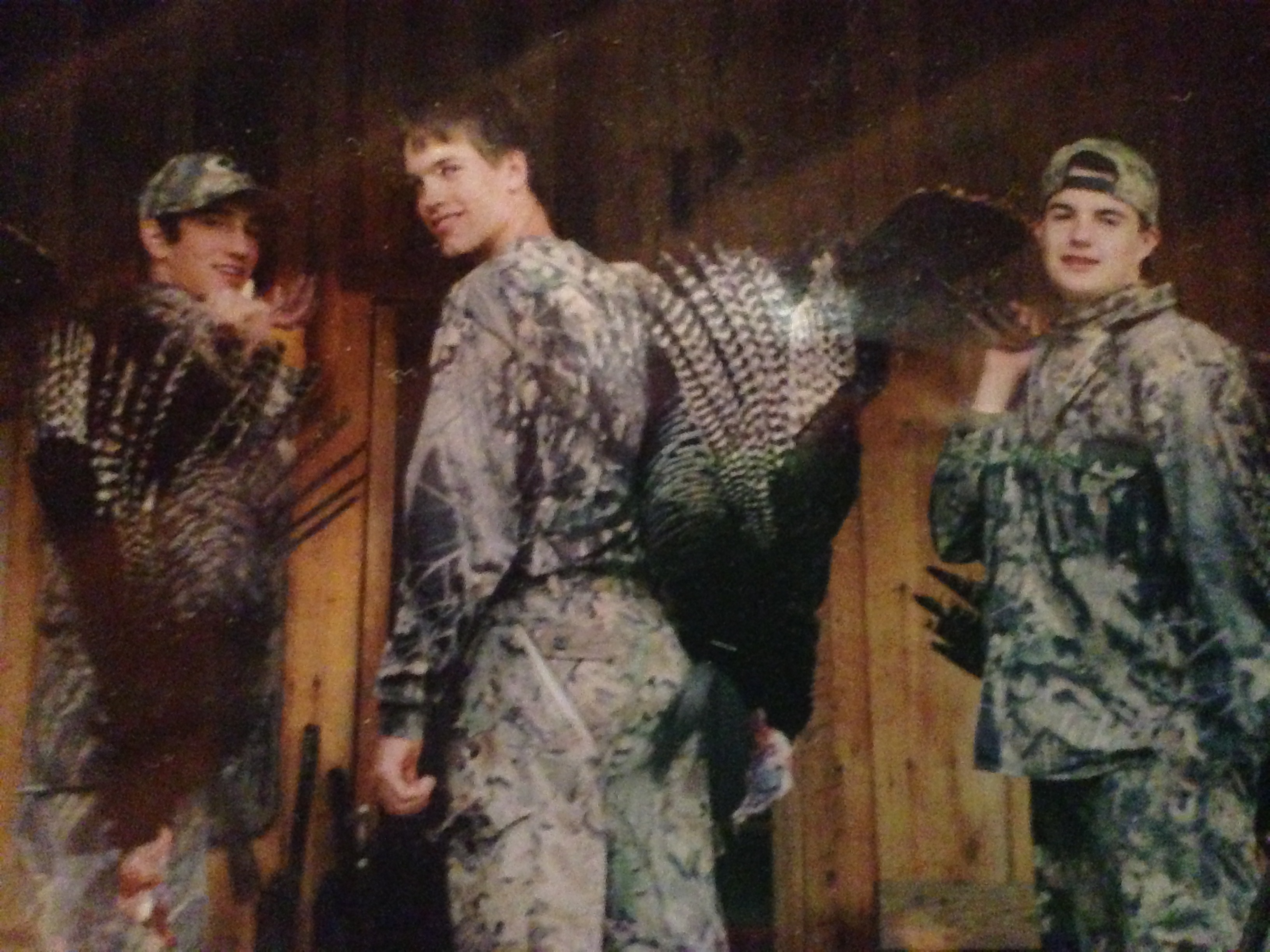

We stand on the porch at mid-morning. I’m in the middle. My friend Josh is to the left. He and I are quartered away from the camera. This was a popular pose in the 90s and not just for hunters. Kyle stands on the right, facing me, at a half turn. Three dead toms hang across three bony shoulders. My dad, behind the camera, stands down in the yard.

“Look at those shit-eatin’ grins!” he chortles. “You boys done good.”

Kyle killed his early, just off the roost, as I had done with both of mine. He called his bird across a shin-high winter wheat field and shot him at 20 paces when the tom came out of full strut by his decoy. He was good from an early age with the diaphragm calls. Could cut, purr and keekee with the best of them.

Josh wasn’t as fortunate. He’s holding one of my two. And still, none of us could believe it’d happened that way. Dad cooks breakfast while we clean the birds and I tell the story for the third time...

Dad could hear the drum beats too I suspect because he’s calling a bit more aggressively. The H.S. Strut Push Button Yelper is a pretty simple contraption. All you do is push a little button that slides a wooden plate across a piece back and forth and makes pretty much any turkey call you want. The great thing about the fighting purr is that it makes aggressive gobblers believe there is a ruckus happening and they need to get involved because ten times out of ten during the spring it’ll be about a hen. And so they come to the fight to win a hen. That’s the prize.

Dad keeps pushing the button and the gobblers keeping drumming and gobbling and they sound as if they’re getting closer until mysterious black half ovals begin cresting the rise. Could be skunks. But instead, it’s strutting toms. I quickly count six! We have a decoy sitting about 15 yards in front of me and they are dialed in. My breathing is erratic. So are my eyelids even though I’m trying not to breathe or blink.

The great wobbling bodies finally reach a point just beyond the decoy where I know I can make a shot. So I pick out a single white-blue-red head and look down through the sites of my Mossberg. Dad hits the call again I think just for the sake of watching six gobblers all hammer back at once which they do. It’s incredible. But I can’t let the show go on much longer. The pressure is too great.

I jerk the trigger and the shotgun thunders and crashes against my shoulder. Those dang three-and-a-half-inch turkey loads are hell on the shoulder. Four turkeys are flying. Two are flopping. Somehow I’d managed to kill two toms with one shot. It’s an absolute miracle. Hopefully one of them was the one I aimed at. Hopefully the other just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, for his sake. Or maybe I really did just take hold of the trigger and grip it and rip it and send hot lead into the group and hoped to come away with something. It’s hard to remember looking back.

And it’s hard to imagine going forward that we should ever witness such a spectacle again on the little farm. Of course, who knows, we’ve seen deer numbers dwindle and rebound. Rabbits too. And we have yet to kill a single coyote. We’ve trapped a few raccoons but not enough that could possibly make a difference. What I do know about the future is that there will be a spring and the opportunity to sit in the woods with my dad and friends and look at all the fine things happening around us. Sometimes you get to save the cost of an extra shotgun shell. Always you get lucky by simply being there no matter the outcome.